Archival Spaces 334

Ivo Blom’s Quo Vadis?, Cabiria and the Archaeologists

Uploaded 10 November 2023

In 2005, I published an article, “The Strange Case of the Fall of Jerusalem,” which won the Katherine Singer Essay Award and dealt with the archival identification of a biblically-themed film that was only known by its American States Rights release title. In describing the archival process of identification, I researched Italian costume epics from the pre-WWI era, thinking the film could be Italian and pre-war, before finally discovering it was a German film, Jeramias (1923, Eugen Illés). In that research, I also learned what a huge impact Italian costume pictures, like The Last Days of Pompeii (1913) and Cabiria (1914) had in America, actually forcing U.S. producers to switch to feature-length films, rather than continuing to make shorts, as dictated by the Motion Picture Patents Company. I was therefore particularly interested in Ivo Blom’s new book, Quo Vadis?, Cabiria and the Archaeologists. Early Italian Cinema’s Appropriation of Art and Archeology (2023, edizione Kaplan) which quite unexpectedly discusses the amazing level of sophistication of these early cinematic representations of Roman and Carthaginian antiquity.

In his introduction, Ivo Blom identifies the 19th-century historical genre painters Jean-Léon Gérôme, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse, and Henrí-Paul Motte as the archeologists of his book title. These insiders at the Paris Art Salons, at least for a while, used actual archeological objects to create a visual world of Roman antiquity that has entered into the collective imaginary, recycled, reused through a multitude of media, like Gérôme’s Pollice verso (1872), which has reverberated through our images of not only a Roman gladiator arena but the very idea of thumbs up or down. Ivo Blom defines that kind of channel-hopping in terms of transnationality and intermediality.

One of the ironies of the early Italian cinema’s appropriation of paintings by Gérôme and other realist-trained painters of historical subjects was that by the time filmmakers borrowed their iconography for mise-en-scène, costumes, sets, and props, these painters had been out of fashion for at least two decades; their reuse in the new medium actually increased media presence. Thus, in his first chapter, Blom demonstrates how certain painted images of antiquity wandered from the easel to the operatic stage, to book illustrations, to postcards, to advertising, to magic lantern shows, so that Enrico Guazzoni and Giovanni Pastrone would not even have had to see Gérôme’s paintings in the flesh – although that possibility is also documented, – but only one of the many reproductions in circulation. Indeed, the early Italian epics were not the first cinematic form to appropriate historical paintings, Blom discusses the preponderance of so-called tableaux vivants or living pictures, which were popular as stage attractions and in cinema around 1900.

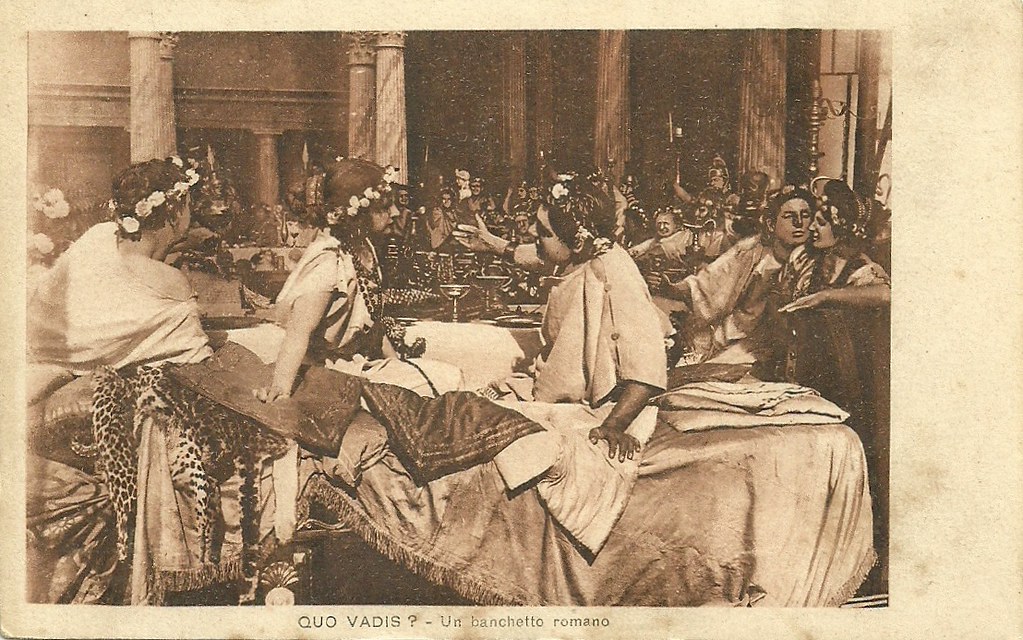

Henryk Sienkiewicz’s 1896 novel, Quo Vadis, was published in numerous illustrated versions in Italy before Enrico Guazzoni and the Italian Cines company released their film, Quo Vadis (1913) which included reproductions of Gérôme’s paintings. The first film version of Quo Vadis (1901), produced by Pathé and co-directed by Ferdinand Zecca, also quoted Pollice verso, as did Luigi Maggi’s The Last Days of Pompeii (1908), Stuart Blackton’s The Way of the Cross (1909, Vitagraph) and subsequent versions of The Sign of the Cross by Edison (1914) and Cecil B. DeMille (1932). Blom argues that Gérôme’s paintings were in fact proto-cinematic in their construction of space and therefore imminently adaptable to cinema.

Another major influence on Guazzoni’s Quo Vadis was the paintings of Alma-Tadema in terms of staging, and “particularly the use of props and deep staging.” (p. 108) Like other painters of antiquity, Alma-Tadema made use of actual archeological objects from Roman times, especially furniture and other props. which then entered into the visual vocabulary of Guazzoni’s film and other Italian epics. Alma-Tadema’s composition in deep space also became a visual feature in many Italian silent epics, which layered space through set elements like curtains and stairs.

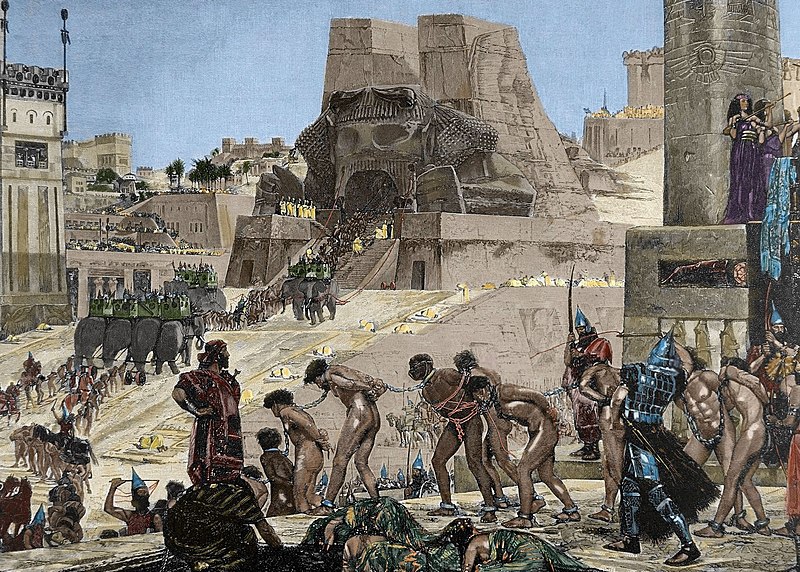

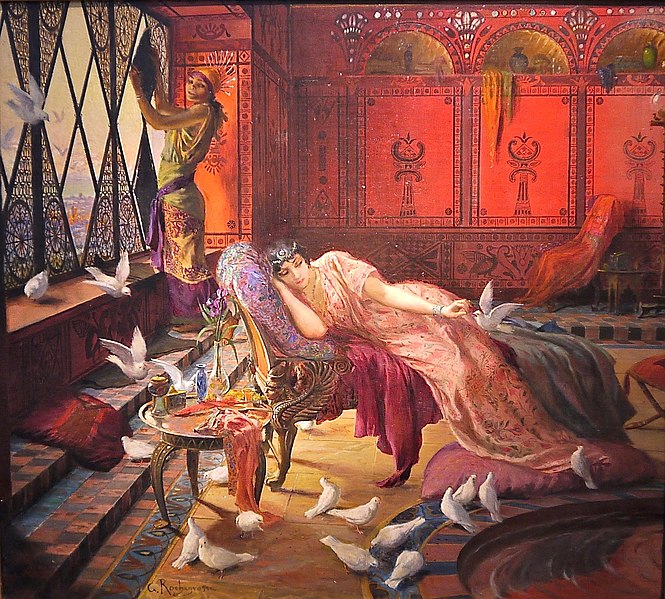

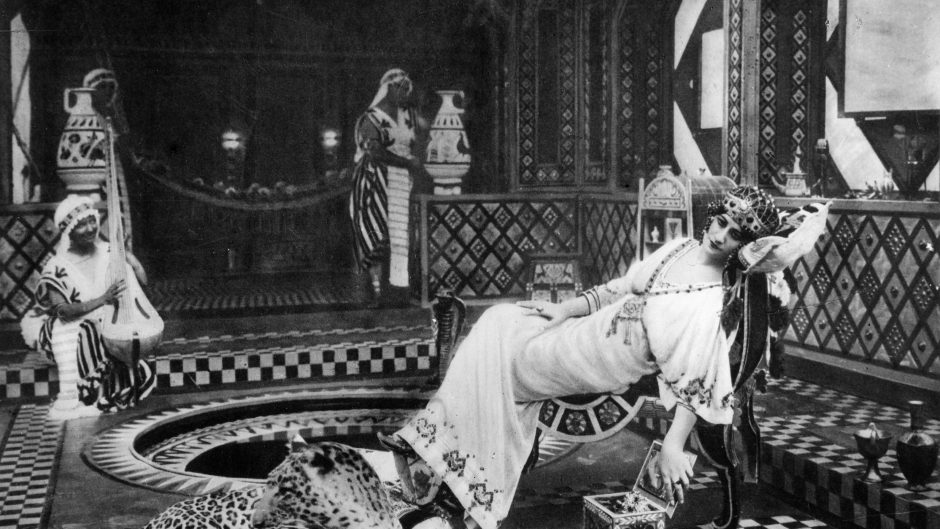

Giovanni Pastrone’s Cabiria (1914), which Blom considers “the apex of the historical genre in early Italian cinema” (p. 169), likewise, gives evidence of a rich iconography from previous sources, including the illustrations by Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse for the 1900 edition of Gustave Flaubert’s 1862 novel, Salammbô. Blom zeroes in on two set pieces, the Temple of the Moloch and the boudoir Sophonisba, both also described by Flaubert, to demonstrate how their iconography originated in earlier 19th-century sources, including paintings and opera stagings. Apparently, more than sixty “academic” paintings took their themes from Flaubert’s Salammbô. Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse’s Salammbô et les colombes (1895) functioned as a model for Sophonisba’s boudoir, while numerous other illustrations by the painter were also referenced in Cabiria.

In a final chapter, Blom doggedly researches the Carthaginian, Egyptian, and Roman collections in Italian and French archeological museums, finding that the painters used these sources for specific depictions of objects, while Pastrone owned a printed source of Carthaginian objects, now housed at the Museo del Cinema in Turin.

This is an incredibly well-researched and fascinating book at the intersection of cinema, archeology, and art history; its detailed footnotes alone could fill another book. A must-read for anyone interested in Italian and/or silent cinema, it proves once again the degree to which even popular entertainment cinema in the “transitional” era strove for aesthetic legitimacy through references to art and literature.