Archival Spaces 331

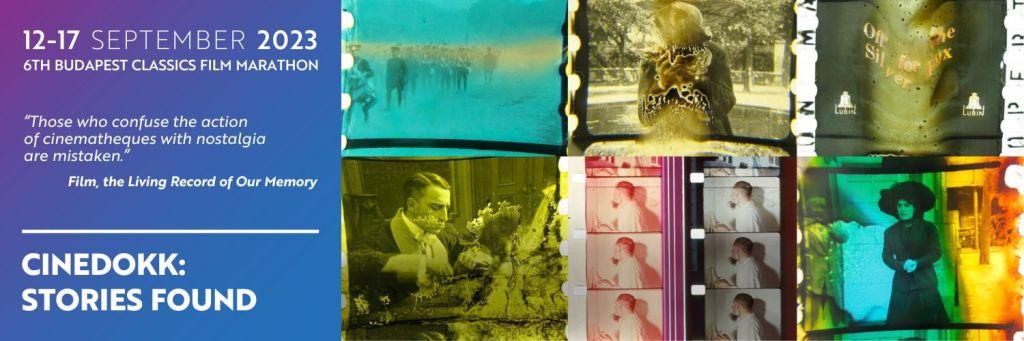

Budapest Classics Film Marathon

Uploaded 29 September 2023

The 6th iteration of the Budapest Classics Film Marathon happened from 12 – 17 September with an eclectic mix of restored films, 48 of them to be exact. The Festival this year featured a focus on Hungarian filmmakers abroad, Alexander Korda, Emeric Pressburger, and Andre de Toth, but also the work of Andrew and Kevin McDonald, Emeric’s grandsons (Trainspotting, Last Kind of Scotland), Gazdag Gyula – my former colleague at UCLA -, Hungarian women directors, Kinuyo Tanaka, Sports films, Films about cinema, animation, and the grab bag Open Archives. Curated by National Film Institute Director, György Ráduly and his team, the Fiilm Marathon program strategy has been ever more successful, drawing huge crowds and sold-out theatres. There was also a three-day symposium, two days dedicated to archival work, one day film history, focusing on Hungarian filmmakers abroad. In the interest of transparency, I should note I was invited to Budapest to participate in that symposium.

“Familiar Strangers,” as the morning session was titled, opened with Steven Kovács guiding the audience through the truths and fictions in the biography of André de Toth, who fled Hungary in 1939 and became a cult director in Hollywood, turning out crime dramas and westerns with style, despite B-film budgets. There was a lot of discussion, spilling over into cocktail receptions of whether Endre Tóth was Jewish, half-Jewish, or not-Jewish; no final conclusion. Catherine Portuges followed with a talk on de Toth’s None Shall Escape (1944), the only wartime anti-Nazi film to visualize explicitly the Holocaust. Next, Galina Torma discussed art director Marcell Vértes, who began his career as a cartoonist in Budapest and would win an Oscar for art direction for Moulin Rouge (1953).

The afternoon session, “The Kordas and their Circle,” included talks by Josephine Botting on archival traces of Alexander Korda in the British Film Institute’s collections; Korda’s career began in Hungary in the 1910s, moved between Berlin, Paris, and Hollywood in the 1920s, and settled down in London as one of the U.K.’s most important producers, the founder of London Films, after the worldwide success of The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933). Ágnes Széchenyi discussed the similarly meandering career of Lajos Biró, an exceptional Hungarian scriptwriter who worked for Korda and Ernst Lubitsch. Finally, Ferenc Takács discussed the British cinema’s nationalistic fantasies of Empire, directed by the Hungarian emigre Zoltán Korda, Alexander’s younger brother.

What this mini-symposium (and corresponding films in the program) demonstrated was that while there has been much research on Russian film exiles from 1917, and on German émigrés from Hitler, little has been published on Hungarian refugees, probably because most were viewed as economic immigrants, rather than as forced emigrants. Many Hungarians, like Korda, Michael Curtiz, Victor Varconi, Moholy-Nagy, and Bela Balasz fled after the failure of the 1919 Hungarian Communist revolution, others, like Steve Sekely, Lici Balla, Szöke “Cuddles” Szakall, Ladislaus Fodor, Emerich Kálmán, Alexander Laszlo, Lili van Hatvany, Andrew Marton, and Joe Pasternak, after anti-Semitic laws in Hungary barred them from employment. After the conference, Steven Kovács sent me his piece, “How Did Hungarians Do It? The Hungarian World of Ernst Lubitsch” (Bright Lights Film Journal), in which he argues that the contributions of Hungarian writers have been undervalued in Hollywood historiography, including writers, like Ferenc Molnár, Lajos Biró, Melchoir Lengyel, Ernest Vajda, Géza Herczeg, Miklós László, and László Bús Fekete. Furthermore, Hungarians penetrated all the Hollywood film professions, whether Bela Lugosi (actor), Laszlo Szusc (agent), George Pal (animator), Erno Metzner (art director), Miklós Rózsa (composer), Leslie Kardos (director) or Ernst Matray (choreographer). Then … there was a whole other group of Hungarians who made German films for the Third Reich, like Géza von Bolváry, Arzén von Cserépy, Josef von Báky, Marika Rökk, and others. Co-curator of the Marathon, Janka Barkóczi, has identified more than 800 Hungarians working in the film industries of Paris, Berlin, London, and Hollywood.

Thanks to the hospitality of the Hungarian National Archive, I attended a McDonald family screening of The Old Scoundrel (1932), Emeric Pressburger’s only Hungarian language film, and his last UFA film, before he emigrated to England. The film is a charming if stereotypical story of life on the Puszta with a faithful old bailiff squirreling away the money of his gambling-addicted Baron, and being accused of embezzlement, when in fact he has saved the fortune for the Baron’s daughter and heir. After the film Kevin and Andrew McDonald wondered how to interpret what or may not have been an anti-Samitic remark in a film written by their grandfather. A sentimental and nationalistic affair, the German version, Es leuchtet die Pusta was not released until February 1933 with much the same cast. Its female lead, Rose Bársony, however, would be fired by the UFA on 29 March 1933, along with two dozen other Jewish employees, while Hungarian star Marika Rökk would become UFA’s “Nazi Ginger Rogers.”

André de Toth’s Two Girls on the Street (1939) follows the fate of two young women, one who works as a musician in an all-girl band after being disowned by her family due to an unwanted pregnancy, the other a peasant who comes to Budapest for work. Seemingly proto-feminist, it’s mitigated by the fact that the young farm girl is nearly raped by an engineer at the construction site where she works, then falls in love with him with a happy end: marriage. Not to mention the fact he’s at least fifteen years older. Much of the film was shot on location in Pest’s Újlipótváros district, which experienced a housing boom in the 1930s, featuring much modernist architecture influenced by the Bauhaus.

I was also happy to see Viktor Gertler’s State Department Store (1952), a Stalinist propaganda musical-comedy about a Budapest Department Store whose empty shelves are blamed on the CIA. Gertler had also been sacked in the infamous March 1933 meeting of the Ufa Board, despite having edited Ffa’s biggest moneymakers (Drei von der Tankstelle, Congress Dances). He moved back to Hungary the same year and started directing, but was blacklisted again as Jewish in 1937, living illegally in Brussels during World War II, then returning to Communist Hungary, where he resumed his career as a prolific film director. Despite its propagandistic elements, the film was not without charm, light-hearted with lots of singing and dancing along the Danube.

Finally, I caught two documentaries by Gyula Gazdag, The Selection (1970) and The Whistling Cobblestone (1971), which were amazing for their biting critique of Communist society. The short visualizes the selection process for a band for a Party event, while the feature concerns a group of high school boys who volunteer for a labor camp in the countryside, but are left hanging without work, because of absolute mismanagement. Both films reveal the astounding level of everyday corruption under Communism, the latter film being banned, but then released to become a cult film, championed by younger generation Hungarians. My teaching colleague, Gyula Gazdag taught for years at UCLA, before retiring in 2015 to Vienna, so I was delighted to see him again.