Archival Spaces 323

Hugo Haas Exhibition

Uploaded 9 June 2023

A new small but informative exhibition on the Czech-American actor-director, Hugo Haas, opened on 25 May in the waiting room of the Consulate General of the Czech Republic in Los Angeles. While several recent Consul Generals have been active in promoting Czech Film Culture – the annual “Czech That Film” Festival recently completed its 11th iteration – Consul Jaroslav Olša, Jr. has been particularly active, being himself an avid and active film historian and collector. He has mounted several exhibitions, including now “Hugo Haas in the US 40-62,” which includes film stills, posters, and letters from the collection of Milan Hain, a Professor of Film Studies at Palacký University who recently published a biography of Haas in Czech.

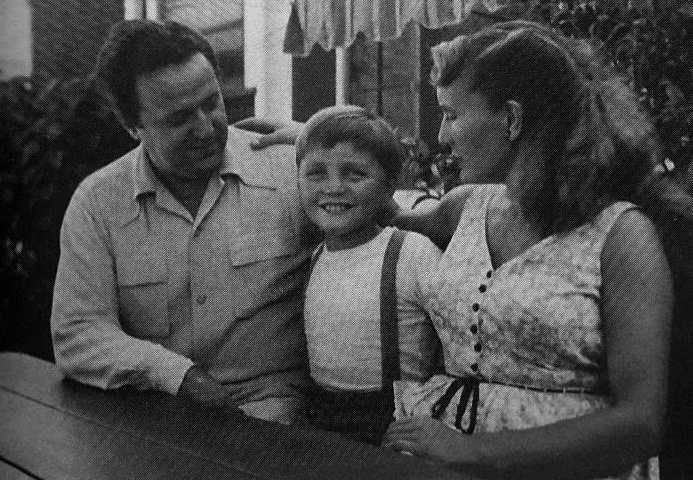

The thesis of the exhibition is that Jewish-born Haas was traumatized by both his exile from Czechoslovakia in 1939 and the murder of his beloved brother, the gifted composer Pavel Haas, and father in Auschwitz and Theresienstadt, respectively. As a result of that trauma and depression, the director’s wife, Maria Bibikoff, eventually left him, after he became infatuated with his leading actress, more than twenty years his junior, Cleo Moore. Most of his independently produced melodramas are variations on the theme of older men, played by Haas himself who form liaisons with much younger, often amoral, very blonde and buxom women.

Born in Brno in 1901, the second son of Lipmann (Zikmund) Haas and his wife Elka (Olga), née Epstein, Haas’s Jewish family was Czech speaking, rather than German, the lingua franca of most Czech Jews. He began his career as an actor at the National Theatre in Brno in 1920. Four years later, after stops in Ostrava and Olomouc, still in the Moravian hinterlands, he moved to Prague to the Vinorhady Theatre, and in 1929 to Prague’s National Theatre, where he remained until his abrupt firing in March 1939, after the Nazis had invaded Czechoslovakia. He appeared mostly in classics by Strindberg, Ibsen, Dostoyevsky, Shakespeare, Marcel Pagnol, and Shaw, but his most famous role was in Karel Čapek’s “The White Sickness,” in the pivotal role of Dr. Galén, which the author had written specifically for him. Haas also starred in the film version, Skeleton on Horseback (1937), which he also directed. (See my blog about the film https://archivalspaces.com/2021/12/04/242-hugo-haas-the-white-sickness/) When one night, a drunken Nazi took a shot at him, he knew it was time to leave the country.

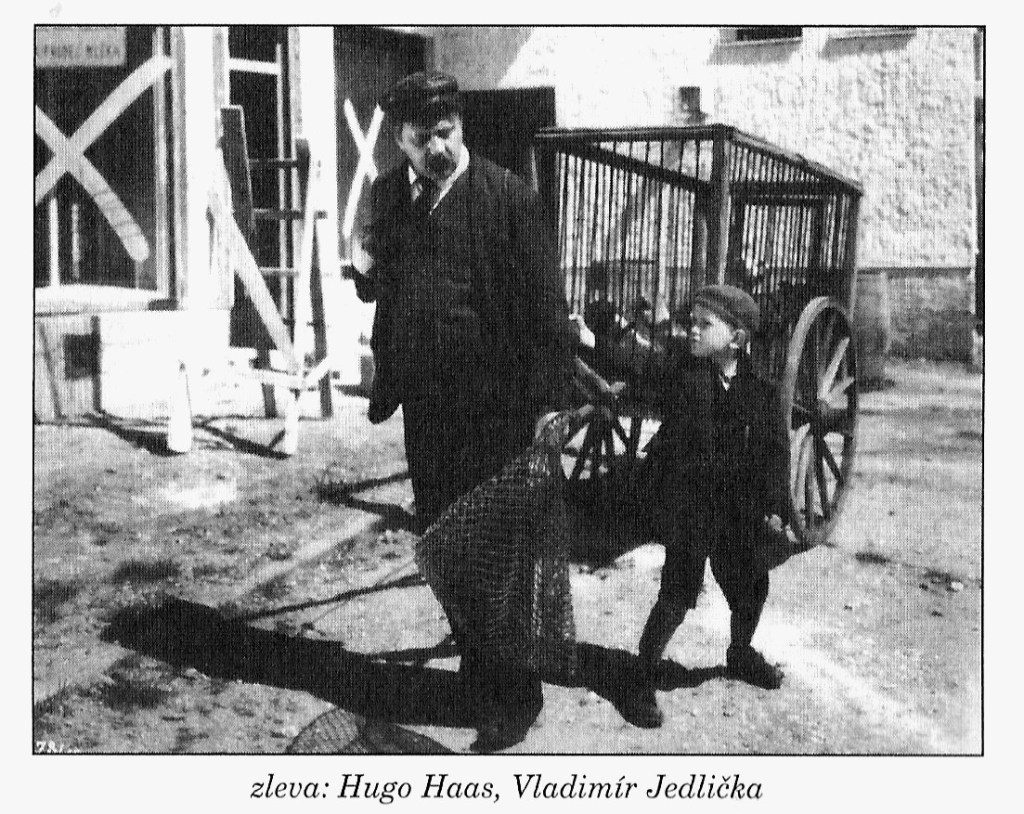

Haas’s film career began in Czech silent films in 1925, appearing in a bit part in a bio-pic of the Czech national dramatist, Josef Kajetán Tyl (1926, Svatopluk Innemann), before starring in a comedy, The 11th Commandment (1925). However, Haas only hit his stride with the coming of sound, playing a supporting role as the chief physician in the first sound version of Hašek’s classic novel, The Good Soldier Svejk (1931, Martin Frič), and also starring in more than two dozen comedies, including Sister Angelika (1933), Life is a Dog (1933), and Long Live the Deceased! (1935). Haas played mostly mature characters, often professors, and factory owners, even when he was the romantic lead, given his stocky build and a face that could hardly compete with the matinee pretty Francis Lederer; in two films he is a generation older than his love interest. By 1933, Haas was also working behind the camera, completing fourteen films as scriptwriter, and six as director, including Screen (1937), Skeleton, and Girls, Stand Fast (1937), before exile cut his career short. As in that last-named film, Haas functioned as director, writer, and star in his remaining late-30s Czech films. Forced to flee his home, Haas worked to return to that rare cinematic trifecta; it would take him twelve years.

Hugo Haas was 39 years old when he reached New York on 6 November 1940 on the S.S. Cambion, after traveling the Jewish refugee trail from Prague to Paris to Lisbon with his wife, Bibi, but without their child Ivan who was too small to travel and left with Bibikoff’s sister. They would be reunited only after the war but remained estranged, the sickly boy calling his aunt “mother.”. In New York, Haas tried to work in theatre, appearing in “The First Crocus” in New York, which closed after five days on Broadway in January 1942, but it got him an acting job in Hollywood.

His first role was in a supporting role as a Russian resistance fighter in the anti-Nazi film, Days of Glory (1944, Jacques Tourneur), opposite Gregory Peck in his first role. Haas played another Russian in the adaptation of a Chekhov novel, independently produced by German émigré Seymour Nebenzahl, Summer Storm (1944, Douglas Sirk). Slipping into smaller, accented character roles the rest of the 1940s, Haas played a Caribbean innkeeper in The Princess and the Pirate, an Italian priest in A Bell for Adano, a friend of the murdered exiled writer in Jealousy (1945) – directed by fellow Czech Gustav Machetý -, a French village Mayor in What Next, Corporal Hargrove (1945), a film director in Merton of the Movies (1947), etc. By 1951, he had apparently earned and saved enough money to produce, direct, and star in Pickup, a low-budget melodrama from a story by his Czech friend, Josef Kopta, shot for a song ($85,000).

Unexpectedly, the film was sold to Columbia more than a year after its completion, earning Haas a tidy profit, while the studio grossed over $ a million. German émigrés Arnold Phillips (script), Douglas Bagier (editor), and Rudi Feld (set design) also worked on the film, the last named becoming a member of Haas’s team on nine films. Starring Beverly Michaels as the platinum blonde femme fatale out to murder her much older husband, Pickup made the unknown actress a minor star, leading to a rematch with Haas in The Girl on the Bridge (1952), where she plays a suicide rescued by an older Holocaust survivor who then marries her. Phillips, Bagier, and Feld also worked on the second film, as did Robert Erlik, a Czech refugee who would co-produce eleven films with Haas. Many consider The Girl on the Bridge a minor masterpiece, which, like Pickup was made for under $100,000 and thereby turned a profit.

With Strange Fascination (1952) Haas discovers Cleo Moore, another buxom blonde whose only claims to fame were starring in a poverty row serial, Congo Bill (1948), and being briefly married to Louisiana Fascist Huey Long’s son; the marriage lasted six weeks. Haas plays a European pianist who is seduced and wed by tramp Moore, mutilating one of his hands when she leaves him for a younger man. Haas made seven films with Moore, all variations on the same theme, although in some cases, the director is not the victim but a perpetrator, as in the case of Bait (1954).

Before retiring to Vienna in 1961, Haas completed no less than fourteen films, invariable producing them himself before selling the distribution rights. Many were variations on the same old theme, not all of them successful, despite the low budget. He returned to comedies only once with Paradise Alley (1962), which flopped after sitting on the shelf for four years. His best late film was Lizzie (1957), which starred the great Eleanor Parker as a woman with multiple personality disorder, was distributed by MGM, while Parker was expected to be an Oscar nominee; unfortunately, Joanne Woodward was nominated for the similar The Three Faces of Eve (1957) and Haas’s film was forgotten. He died in Vienna in 1968, having returned to his homeland only once for a brief visit.

One thought on “323: Hugo Haas”